Last night, the available ICU capacity in the counties that make up the state’s new definition of “Southern California” dropped to 13.1% — a decrease of 7.5 percentage points from the previous day.

This is happening in a terrifying context in LA County: almost every metric of the pandemic’s severity is picking up speed right now.

Three weeks ago, there were 966 people hospitalized with COVID in the county, and about 2,500 new cases a day. At the time that was cause for mild panic — it was a significant increase from what we’d been seeing a few weeks earlier, and public health officials started sounding the alarm and urging people to stay home.

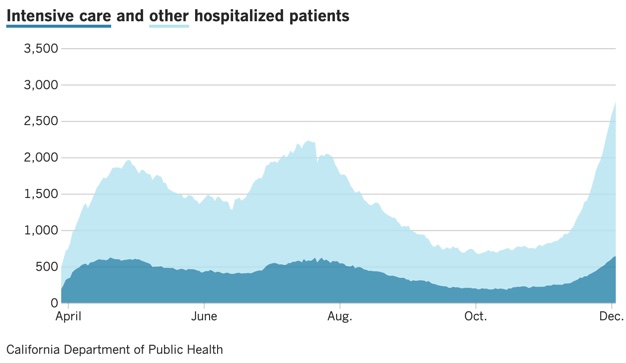

Yesterday there were 2,668 people in the hospital and 8,860 new cases. Both are records. We will set new ones when the updated numbers come out this afternoon. This is unequivocally the most dangerous moment of the pandemic, and things are getting worse even faster every day.

And yet: the restrictions we’re under right now, and even the ones that we’re planning for next, and are more lenient than they were in March. Some people are calling what we’re under a lockdown, but it looks different than the last one:

- Almost all retail stores were closed from March until May. They’re open right now at reduced capacity, with no announced plans to close them.

- Nail salons, barbershops, and tattoo parlors, closed for indoor operations from March to October, have stayed open even as the spread of the virus has been accelerating for over a month (they close again tomorrow).

- Film production, shut down from March to June, is up and running.

Maybe unrelated, but I also haven’t heard anyone in my neighborhood yell out the window or bang pots at 8pm for about two months.

It’s obvious why a lot of businesses are being allowed to stay open: if they close, they will fail. The new apex of the pandemic is coinciding with the most financially essential time of year for just about every retail operation. Black Friday is called that because it’s the day a lot of retailers go into the black — that’s less true now with the rise of online shopping, but even increases in online sales weren’t enough to make up for lost in-store visits this year. Any small business that was near a precipice would probably get shoved over it by a full closure in December.

We also don’t have enough financial assistance in place to support newly-unemployed workers. Boosted unemployment payments kept the entire economy afloat for months — those are now gone or going away, though it looks some more federal aid might be coming. Under any circumstances, a lockdown would force a lot of workers into desperate financial situations, causing some people to take gigs that might make them more likely to contract the virus.

Meanwhile, sitting on the other side of the pressure gauge are people like me — the fortunate people for whom it is very, very easy to call for a lockdown. I work from home and the small business that I run does not exist in physical space. Getting a haircut is not a meaningful experience for me. A lot of nights I feed myself by pushing a button, at which point something happens somewhere else and a hot bag appears outside my front door. A real lockdown would have virtually no effect on my life.

But I’m also not the kind of person the existing policy is putting in the overloaded ICU system. Here is a chart showing the ethnic breakdown of admissions in to public hospitals in LA County:

Latinos make up about 48% of LA County’s population. Every other ethnicity in that pie chart is underrepresented — but Latinos are hospitalized in the public system at a rate about 53% higher than normal. Latinos are also getting sick and dying of COVID in disproportionate numbers. And the county hospitals already see longer waits and worse health outcomes than private providers.

That chart tells a story about overcrowding in homes, the populations served by private hospitals, ineffective government messaging, and financial need forcing people into life-threatening situations. We’re also talking about a Latino population that is 17% uninsured — more than double the uninsured rate of white, Black, or Asian residents.

Hospitals will be completely full in days. There are only 26 open ICU beds available in the public system, and 76 overall. We’re going to start seeing care rationing, both for COVID and non-COVID patients, as other health providers around the country have implemented. More medical workers will get sick, which will affect already-strained staffing numbers.

And all of this could easily be a best-case scenario: if infection growth keeps accelerating, the system overload could be faster and more devastating than even doomsayers are predicting, as we head into yet another holiday where people will gather. Meanwhile, government officials are signaling their continued intention to rely on reactive policy — we will keep putting up levees after it starts to rain.

But what if we did go back to the March standards — nonessential retail, film production, the court system, and other indoor operations being fully shut down — for two weeks starting now? Would that send a signal of appropriate urgency? Maybe communicating to people how important it is to stay home — and at least giving them fewer places to spread the virus if they refuse?

Would a full lockdown keep more workers healthy and alive? It wouldn’t be enough to head off our current pending disaster — but would it shorten its timeline and limit the damage? I’m not a public health expert or an economist, but I wish one would tell me why the harm of implementing a two-week shutdown of all indoor business would be worse than what’s coming to us if we don’t.

There are probably quiet, back-room conversations where powerful people are making arguments against a real lockdown that they’d never say out loud. Like: cases and deaths will rise whether business shuts down or not, because people will just gather in their homes — and if thousands are going to suffer and die regardless, we might as well keep the malls open.

That might be true. There are definitely no good solutions or transparently correct answers: we don’t have legitimate contact tracing so it’s hard to even know exactly what is causing cases to rise like they are. We might be fucked in every direction and in all timelines.

But if there is a chance that different policy could save thousands of lives at the cost of severe economic impact, do the public institutions that exist to protect us have the obligation take that chance? And if they do, how could the moment possibly not be now?